IN CONVERSATION WITH: Vix Chandra

Interview by Shanita Lyn.

Photo by Frederick Nilsson.

Vix Chandra is a Malaysian rapper, creative strategist and absolute gem of a guy. You may know him better as Sayla, or one half of Dose Two — but none of these brief descriptions really sum up who he is as a person. I first met him back in 2015, when we were both on the creative team behind Sand: The Musical, and he very quickly became one of the few people I truly respect and admire. Humble, confident, creative, prolific, multi talented, hardworking, down-to-earth, genuine, funny, driven… He was an absolute joy to have on the team, both professionally and as a friend.

I’ve been meaning to sit down and have a proper conversation with him since I first got to know him, and now, five years later, I finally had the chance to do so. I caught up with Vix over Zoom to ask him some questions on creativity, music, fatherhood, racism, change and his hopes for the future. You know how they say don’t meet your heroes? Well, I can assure you that that sentiment does not apply to Vix, because this chat did not disappoint.

Vix was born on Penang Island and grew up in Taiping, a small town in the north of Malaysia. “I came from a very modest family background,” he says. “We weren’t rich — both of my parents were government servants, we lived in a quarters, went to government school… I think it was very ordinary, a very Taiping life, I have to say.” Even from a young age, he showed signs of creative flair. “I did a lot of imagining and drawing and writing, even as a kid. I watched a lot of TV. I know that’s a bad thing, but I think it did me more good in the long run.” His critical eye for the media he was exposed to would eventually point him towards a degree in advertising — it was either that or architecture, he says, and the maths component of the latter decided it for him.

He moved to Cyberjaya to study advertising at Multimedia University (MMU), where he got his first taste of big city living. “I think if you grew up in a small town like me, the city’s like the Wizard of Oz, you know?” he explains. “Like, if you made it in KL, you’re the shit! But also, when you go to the city, when you come from a small town, you have a place to go back to. It’s more of a safety net, that you know that you can always run away from this big city if need be, and go back to something more familiar.” This reassuring fact helped tide him over during his early days in the KL advertising industry, as he tried wearing a variety of different hats in an attempt to find one that fit. “I majored in advertising, and then I graduated, and then I looked for an advertising job. In my head, [I was like] let’s find those jobs where I can wear a suit and make a lot of money. And I became a suit! Which is client servicing, or brand executive. Absolutely failed because I hated it so much. [And at] my internship, I was a graphic designer — also hated it, simply because I wasn’t very good. So copywriting was my only route out. If I failed in copywriting, I would just go back to the Taiping advertising uncle’s shop and print t-shirts.

“Luckily for me, advertising panned out,” he laughs. Panned out is a mild way of putting it. In his work as a copywriter, Vix went on to win a string of awards, including a Cannes Lion in 2011. Having his work recognised and validated on that scale immediately opened doors for him. “Finally [people were] like, ‘Ahh, this Vix guy actually has ideas, because he has an external validation,’” he says, sounding a little resigned. “I have an issue with that. In my head it’s like, ‘I told you guys I have ideas!’ But anyway,” he laughs, “that opened doors, and I basically jumped at the opportunity.” At that point in his life, when his only commitments were his rent, his car payments, and sending money home to his family in Taiping, he had the freedom to go all in. For a few years, Vix lived the “typical advertising life — stayed in the office till ungodly hours.” Eventually he also ventured out into the clients end of things again, with quick stints at Red Bull Global in Austria and Netflix Asia in Singapore, but all roads led him back to advertising. Now, he’s back in Austria, working for one of their biggest agencies and absolutely loving it.

Though his advertising portfolio in itself is no small feat, he also managed to build a formidable music career alongside it. How did he do it, while working such ungodly hours? “Yeah, well… we had very little output during those years,” he laughs. But his roots in music stretch much further back, into his childhood growing up in Taiping. His parents, both certified ballroom dancers, surrounded him with the sounds of ABBA, Boney M., Elvis and The Beatles. His taste in music was also largely influenced by his sister, seven years his senior. “She exposed me to a lot of her music as well when growing up, so with that I’m a huge fan of Nirvana and Oasis, huge fan of Queen… At that age, you know, frickin’ nine-year-old malleable boy, listening to all this rebel music from my sister, I was like, ‘Yeahhhh, this is the shit!’” he grins.

All these musical influences helped shape how he writes, even in his raps — which, interestingly enough, was a genre he hated as a teenager. He had a Poetic Ammo cassette and a Kriss Kross cassette which he enjoyed very much, but that was as far as his appreciation went. “I hated rap, to be honest. Like, in high school, I was exposed to Tupac. I hated it, because I think at that point no one told me that context is very important when you listen to hip hop and rap. Especially for iconic artists like Kendrick Lamar or Tupac, you need to know where they’re coming from, what’s their background, what they’re rapping about, and what they’re rapping against. Cause if you don’t, you just hear a lot of foul words, and [it’s] very aggressive, and you don’t get it. So I never understood Tupac.”

His first real venture into music came in his mid-teens, when a band he was in performed at a Canteen Day stage at the local convent school. “And I came from an all-boys’ school, so that was a big deal,” he remembers with a cheeky twinkle in his eye. “It was amazing! So thank God it went well! And I had my first little tiny taste of fandom,” he laughs. “You know, the next day like, ‘Oh, I heard this girl… she kinda likes you!’ and ‘That girl thinks you’re cute!’ I’m like, ‘Awh, really!’ So that was nice.”

Teen crushes aside, that Canteen Day stage marked his first real performance, and he credits that band he was in as being crucial for him and his music at that stage in his life. “It was when I really started singing — there was no rap in the picture at this point. But we also started writing our own songs, and that’s when I started writing [poetries] as well.” The band continued until its members graduated high school and left for college. Vix joined a few bands in KL while in uni, but couldn’t commit to them properly because of the two-hour bus ride that separated the capital city and Cyberjaya, where he was studying. So for a while, his musical expression was limited to what he could do with just him and his guitar.

At this time, one of his best friends in college was a rapper, and introduced him to a group called Bone Thugs-n-Harmony. “The really cool part about Bone Thugs-n-Harmony is they don’t only rap — they rap and sing at the same time. So their rap has melodies, and they harmonise. So I thought, ‘Oh, I kinda like this, I can sorta enjoy this.’” They would become the gateway group to Vix’s hip hop and rap journey. With his newfound interest in the genre came the desire to try his hand at writing his own raps, just for the fun of it. “When I started I was just messing about. I’m like, ‘Aw, this is like poetry, it’s just, you know, you just gotta read it faster,’” he grins. “I had no clue about cadence back then, or [the] little similes and whatnots that you had to have in there. But it was a good starting point.”

Vix remembers doing a rap version of Badang, the legendary strongman of Malaysian lore, for a university assignment, simply because he didn’t have enough time to do it any other way. “We basically told our lecturer, like, ‘HEY, we’ve come up with a rap for it!’ And they were like, ‘Ohhh that’s great!’ And I’m like, ‘Hah hah hah… ah ha…’” he laughs sheepishly. “So it started just strictly fun, to be honest. I did not intend it to be a craft.”

After university, he started to meet more people who were passionate about hip hop, one of whom was Naqib (otherwise known as QBe), who would go on to become the other half of Dose Two. “We met at a jazz festival in KDU, and we started free styling together, and we were like, ‘Hey, we could chill together.’ And then we also had a little bunch of friends who were also interested in hip hop. Some were DJ-ing, some were into producing, some were singing. So we were like, let’s just start a family!” This musical family is now known as FlowFam XXII, one of the top hip hop collectives in Malaysia. “So in the XXII crew today, we had some really successful artists that came out from there — SonaOne being one, Hunny Madu, Kayda [Aziz], Akeem [Jahat] from Singapore… We also had a member in Sri Lanka. So that was fun.”

Nevertheless, the crazy hours Vix and Naqib kept while working in advertising made scheduling and finding time to make music hard, so Dose Two had to be relegated to the back burner for a while. Although the duo remained intact, Vix started to spend more time writing his own music, which was when the moniker Sayla came to be. Fun fact: “Sayla” is actually based on the word “alias” spelled backwards. “It was an inside joke,” he explains. “It wasn’t supposed to stick, but somehow it did. I couldn’t escape from it. I would’ve given it more thought if I knew it was gonna be a thing,” he laughs. Under that name, he began putting together and releasing his own EPs, the first of which was called Utopian Dreams (2011).

He also took part in a reality contest — 8TV’s WORD Rap Battle — “which destroyed me. After that, everyone just saw me as a very one-dimensional rapper.” At this time, he says, the intention behind his songwriting was also very different than it is now. “In my younger days, there [were] a lot of pieces that [were] penned with very different intent. There [were] songs where we’d write like, ‘I wanna do this song so that other guy hears it and he feels like ah, fuck, I shouldn’t mess with this guy!’ [or] for whatever image purpose, you know? It’s silly, but especially in the rap game, there are expectations of like, ‘Oh, you should front,’ or there are things that you should say. And I’m guilty of doing that, especially in my early days.”

After his reality contest experience, he decided to start from scratch and put together an album that was purely what he wanted to make, without pandering to an audience that was all too willing to pigeonhole him. The result was Conversations with Self & Other Stories (2015), an ambitious collection of twenty songs featuring a diverse range of artists and genres. “I really just went like, okay, so, everyone either thinks I’m a rapper, or thinks I suck, whatever — which is great, because right now I have a clean slate, and I will just purge. So that project was just me purging, and you’ll hear all kinds of stuff in there — like, some songs are not even hip hop anymore. And I was very happy to put that out and basically paint the picture, like, ‘Hi guys, this is me again, and I’m not just a rapper. I just want you to know that.’” Without playing to any expectations, he was able to write with zero inhibitions, and have plenty of fun in the process. “I think the joy of it is actually the process. Like, for me, making music, it’s — the end product is nice to have. Obviously it’s a nice thing to see your album art on Spotify, have people who message you and say, ‘Hey, nice work.’ But that’s never the goal. The goal is actually to express and have fun. Or, sometimes, just to purge something out.”

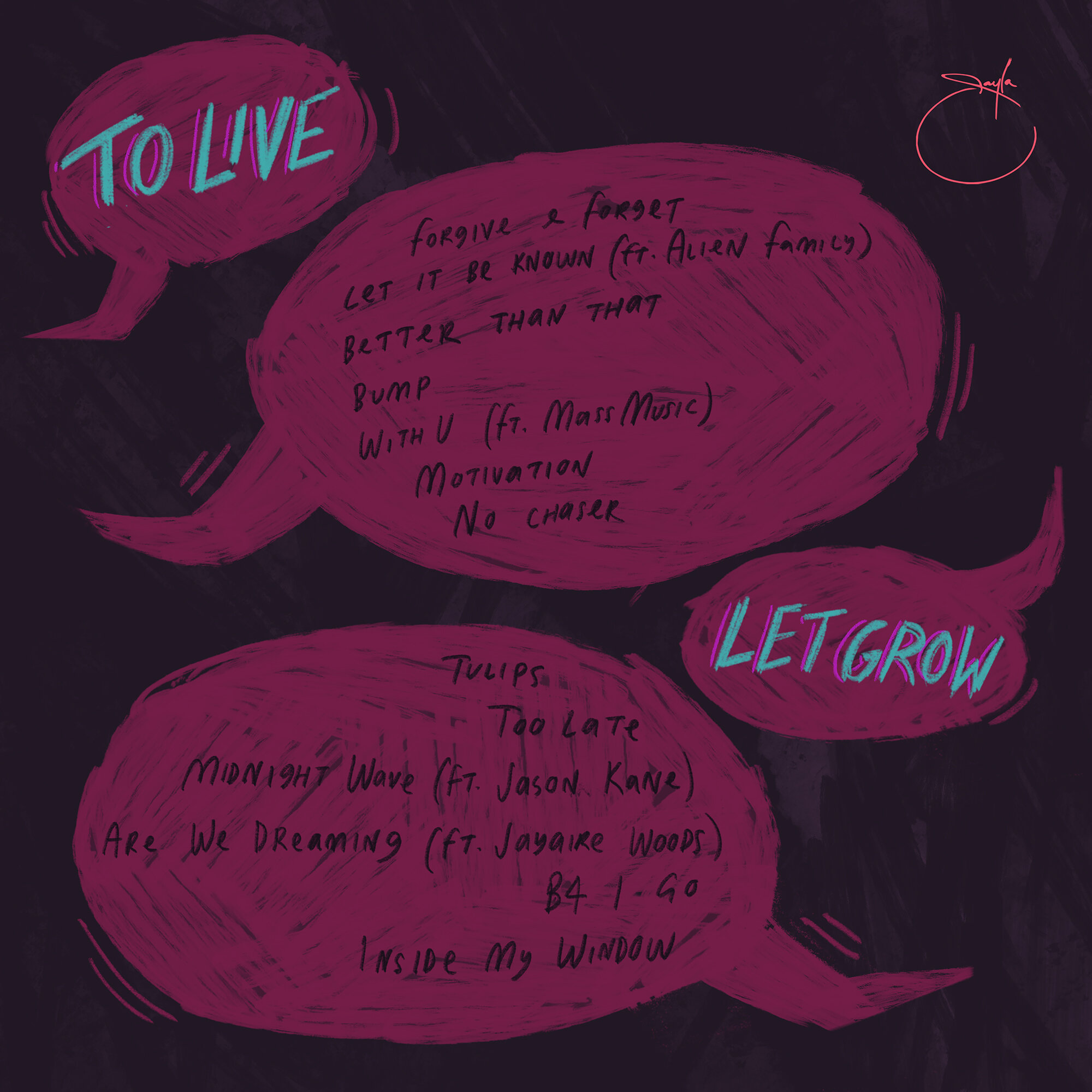

These days, songwriting is a more autotelic process for Vix. Where the messages in his songs were once more braggy and egotistical in nature, intended to create and reinforce a certain image, they have now become much calmer and more introspective. “I think when I’m calm is when I get more ideas. Most of my songs in my catalogue, or even my writing generally, poetry or otherwise, they’re pretty calm in nature, simply because that’s when I get creative and that’s when I write. Like, when I’m really happy, I’d rather be outside doing something happy, like spending time with my daughter, or hanging out with friends, or having a beer or whatnot. When I’m happy I don’t have the urge to, ‘Let’s open the laptop, I wanna write something happy right now!’ It’s really weird! It’s not natural,” he laughs. “So it’s when I get reflective, when I’m quiet, when I read something at night. It could be an article, it could be a conversation I have, or it just could be watching my baby sleep. But then suddenly you start to think about things, and you wanna put it on paper. I have so many voice notes and text notes on my phone, that are just ideas and one liners and whatnot, and sometimes I use them for songs. I don’t necessarily get inspired to just sit down [like], ‘Okay, let’s write a full song right now.’” This explains why most of the lyrics on his latest album, To Live and Let Grow (2020), sound like they’ve come straight out of his personal journal, rather than designed to appeal to a hip hop audience.

He credits this freedom to explore different subject matter and styles to his status as an independent artist. “I think there are labels that tell [their artists], ‘Based on data, the audience today would like to listen to this, this, this, therefore we must write this, this, this.’ I think that’s a really bad practice, simply because if you keep falling back on data, then as a creative you will never expand. But I think there are also labels or A&Rs that understand that it is a creative role.” He cites SonaOne’s latest drop — an album called The Loccdown (2020) which documents his thoughts, ideas and creative process during the COVID-19 induced MCO in Malaysia — as an example. “I think if he was on a very different label, that strictly based on numbers or [didn’t] understand the creative process or [didn’t] have any creative people on their side of things, that album would be shelved. Simply because, ‘Where’s the love song? Where’s the club banger? Where’s the one that will go viral on TikTok?’ And I think that just stifles the whole creative process, really.”

Vix is genuine when he says that he’s happy he’s not signed. In fact, Dose Two were once approached and asked if they were interested in being signed to a label. “And we said no,” he explains, “simply because it was not something that we wanted to do. It was funny, I saw this tweet on the internet by a Malaysian blogger — a hip hop blogger or something like that. And he said like, ‘If you’re not making money from this, why are you even doing it?’ And I think that’s a very popular sentiment out there right now. Like, if your art is not being appreciated by the mass, or you’re not making a lot of money from it, you’re not doing it right. And I think that’s atrocious. Cause if that’s true, we would not get Edgar Allen Poe. We would not get Vincent Van Gogh. We would not get a lot of work that became famous or appreciated way after the time of the artist, you know? Like for Edgar Allen Poe and Van Gogh, they died, and it took decades and decades before people started appreciating their work. So their motivation was not, ‘Oh shit, only one person bought my book today, so I will quit.’ You know? I think that’s a really bad approach.

“I mean, if you’re a ‘full time’ artist,” he continues, “and your goal and motivation is [to] be a billionaire, that’s great, do it. And if you fail, then obviously you’re doing something wrong. But to think that every artist, or every writer, or every poet has that in mind, I think that is wrong, cause that is not how it works. Musicians from Freddie Mercury, to Rod Stewart, to Paul McCartney — they did not first get into music because, ‘Hey, I’m gonna be a billionaire.’ It’s because they enjoyed it, and there was an intrinsic pleasure that they took out from it, you know? And I think a lot of the kids don’t understand that, simply because they’re growing up in a very social world. Like, likes are important, shares are important, so you’re measuring artists and art based on that. But I think that’s a really bad gauge of value. And I think if an artist uses that as a gauge, that is gonna be very depressing, because every artist will go up and will come down. Like, there will be [that] next person that will be more popular for the next generation. [Take] Jay-Z for instance — he was massive during my time, he is still an icon today, but he will not be Migos. He is not the Drake of today. He will not make those numbers ever again. But that does not mean Jay-Z sucks. He’s still making his art — his last album was very adult, and it’s very introspective. So yeah, I think it’s very dangerous when we value ourselves based on what people think, and the type of likes and shares. Especially when it could be rigged as well. It’s crazy.”

Even now, the songs he’s proudest of having written are generally not the ones that do best on the charts and playlists. “Trend is big — having names and meeting expectations. I think the biggest song that’s in my catalogue right now, that’s doing the best on Spotify, is this song called ‘Guadabuda.’ It’s a really catchy song, features some members from my collective, some of them are really big stars, and the topic is [just] mindless bragging. So it’s easy listening, I have to say. You can bump it in your car. Before that one of the bigger songs Dose Two had was called ‘In My Perodua.’ Also easy to connect, it’s all about driving in your Perodua, it’s a silly brag song, it’s not too deep. Which is fine — which is also why club songs are big. You wouldn’t wanna listen to, like, deep lyricism, let’s-talk-about-social-justice when you’re out in a bar, for instance. Those songs are meant for when you are more quiet, when you’re alone, when you’re a bit more reflective.

“So these songs, according to ‘data’, are my more popular songs. But for me, the people that I value listening to my music, they like the songs that are not really trending that high on the playlist. And I think for me, that value means more to me, for someone to say, ‘Hey, I’ve listened to “Keling In Em,” and thank you for empowering us,’ or things like that. And although the numbers for that are obviously much less than a song [like] ‘Guadabuda’, that impact is much stronger. Like, you understand what I’m trying to say, [and] it gets people to talk.”

Songs like “Keling In Em”, “Ape Kill Ape” and “Unwelcomed” are thought-provoking and don’t shy away from sensitive issues, inviting the audience to start having difficult but necessary conversations. The impact some of these songs have had on his listeners went far beyond what he had anticipated. “They stirred conversations in people which I thought [they] would not reach. For ‘Keling In Em’, for instance, a lot of non-Indians messaged me. A lot of Malay friends messaged me as well, basically saying like, ‘Hey, someone forwarded me this, and they said some mean things… and I just want you to know that I defended it by explaining it to them.’ So those kinda things I value so much more, like, yes, that’s amazing, I love that. Then I open Spotify playlists and ‘Guadabuda’ is trending in five cities — great!” He laughs. “Maybe they will continue to listen to my playlist and eventually get to a song that they can connect to. It doesn’t have to be a politically conscious song. If it’s something that empowers them, or inspires them, or gets them to treat their mother better, great. That’s fine. Whether they even broadcast it, I don’t know, it doesn’t matter to me.”

Nevertheless, putting original material out there remains a challenge to Vix, because he’s never confident that the creations he’s most passionate about will be well received. “I’m confident, but I’m not confident. I’m confident that I will like it — I’m not confident whether it makes sense to the rest of the world. So when I write it, when I finish the song, and it’s mixed and mastered,” he holds his hands out in front of him like he’s holding something precious, “or when I’m painting, or when I’m writing, I’m confident enough to say, okay, this is good, this is what I think, this is what I feel. But I’m never confident when putting music out there.” In fact, the man absolutely hates self-promo — a far cry from the “me, me, me” style of rap he first became popular for. This has a lot to do with the autotelic nature of his creativity. “One of the reasons I really suck at self-promo is because sometimes I’m not sure whether I want the feedback. Like, do I want to know what you think of my music? Ehhhhh. Like, I’m pretty sure someone hates it. To be honest I don’t care. I used to care a lot. And then, it came to a point where I think… it comes with age as well. And you go like, it really doesn’t matter,” he reflects. “I hated a lot of things when I was younger, only to grow older and re-listen and re-check them out and finally get it. Like Tupac, for example — hated it when I was 15, by the time I was 25 I loved that guy. I was like, ‘Holy shit, you’re so brave for doing that.’ Same for a lot of things, really. Hopefully that applies for most of the people out there as well. Someone who’s 17 right now might hate my music. But hopefully when he or she’s thirty and has their first child, and listens to ‘Bump’, it makes sense to him or her. And that’s enough for me, I think.”

Upon hearing this, I can’t help but wonder which songs of his he’d like to draw more attention to, if he could. “I think… hmm. I have a lot of songs in the new album that I really like,” he says. “But if you listen to ‘B4 I Go’... the last verse is actually a poem that I wrote easily 15 years ago — it’s called ‘My Feet.’ That for me is my favourite verse, or I think my favourite piece of writing ever, simply because I think it’s simple, but also very personal. I [also] thought ‘Inside My Window’ was really nice. That was one of my favourites as well, simply because — people don’t know this, but when I say ‘inside my window,’ what I meant was actually the window of the screen, the laptop screen. So, all the things that I see through my window.” He traces the outline of his laptop screen in the air to illustrate his point. “Also if you listen carefully in the end, it ends with me exiting the studio and just walking back into the wild. I deliberately left that in there and made that happen, because I think symbolically I wanted to end this ‘Sayla’ thing, and just go back to nature, and go back to who I was prior to this. So [those] two songs, the last two songs in that album, for me, have a lot of value and a lot of meaning.”

Wait a minute — does that mean this is the end of Sayla as an alias? “Yeah,” Vix says simply. “Yeah, the Sayla thing is done. I think it served me really well, I did a lot of things under that moniker. I think a lot of people have different ideas about what that persona meant, good and bad. But yeah, I think I can put it to rest. I think I’m done with it. It was fun while it lasted.” He nods rather solemnly. “I can scrape it off now, it’s done.”

Still, we haven’t heard the last of Sayla just yet. “I have two projects right now in the works — one will still be under Sayla, but these are songs that are either half-written or half-recorded, so I’m just gonna wrap them up and put it out there. They’re not gonna be new songs.” The other project, though, marks a return to Vix’s roots in guitar music — a dramatic departure from the hip hop persona he’s built up over the past several years. “It’s very different!” he admits gleefully. “It’s totally different, it’s really back to like, square one. It’s nice though — I enjoy it, cause I’m finally writing back on my guitar and my piano and my ukulele, and it’s fun. I haven’t done it in so long, simply because I was always like, ‘Okay, how does the hip hop beat come in this one?’ And for this one, the number one rule is NO hip hop. Like, done, like, nothing, nothing. None of that stuff is gonna come in. And we’ll see where it goes. Yeah, it’s gonna be fun,” he grins. “I’ve finished, like, six songs, I think I have another three or four to go. But I also want it to be really special, so I’m gonna take my time with that, slowly crafting it and making sure it’s perfect. And that will be under a different moniker or a different name.”

Regardless of how well-received the final outcome is, though, the creative process is fulfilling enough for Vix to keep making things. Creativity in and of itself has helped him through his darkest times, and continues to be an outlet for all the things he wants to say, but doesn’t know how to. “I think it’s saved my life. Not joking — like, literally saved my life. I think there were a few points in my life where it was very, very dark for me. I was in a very depressive state. Very stupid ideas were running through my head. And having an output — to write, to paint (I used to paint a lot), to sing, to rap, really helps ease that burden. Obviously it doesn’t relinquish it, but it definitely helps. Putting things out there, you feel better. So I think it’s very important, for me personally at least. And sometimes it helped me say things that I can’t really say in person. There are things sometimes [that] I can’t have a conversation about, or it’s too difficult for me to talk about, and I put it in there.”

However, being in advertising, he’s learned to set clear boundaries when it comes to personal creativity and creativity in the workplace. “On an industry level, I’ve learnt it’s very important to set your boundaries. I’ve learned that, when it comes to advertising at least, it’s more of writing from your head than your heart. And when it comes to art, it’s more of writing about your heart than your head. You don’t think about what people think, and you write what you feel. But when it comes to advertising, it’s the other way round. So you need to think of what people will think when they read this, and less on your personal opinion.” He’s also made a hard rule that he will never rap for a client. “Simply because for me, I hold that a bit more sacred. Like, this is my tool to express myself, and I use it for a particular purpose and will not use it for commerce. I’ve done a few raps for brands and companies, but only because the cause [was] closer to home. So [if] it is for a good cause, it’s for something I believe in, something that I can write from my heart, then I’ll do it. But if it’s like, ‘Hey, here’s ten thousand ringgit, rap about Panasonic’s new shaver!’ I’m like errrrrr... I dunno, man. Probably not. But ten thousand though, I might consider…” He laughs.

As we know by now, Vix isn’t one to pigeonhole himself into any one style or discipline. So it isn’t surprising to hear that he’s also keen to test his writing chops in very different fields — specifically, film and theatre. He already has a fair bit of experience in creating video concepts, having come up with the ideas for most of his own music videos thus far. But for the upcoming EP, he’s keen to take it to the next level. “For this last Sayla EP, I want it to be much more elaborate, and I wanna tell a story. So there are gonna be, like, short film kinda things. I would love to also pen a theatre piece one day, like a proper play, one that’s a bit more ‘out there.’ So I’m writing more of these kinda things right now. I have these things in mind, I have concepts, but my first effort will probably be to pen [a] proper story for the next EP. It’s gonna cost, I think,” he laughs. “But let’s see if we can make it happen.”

He’s also keen to get back into painting, a hobby he picked up in college which he has returned to on and off throughout the years. “I used to paint a lot of abstract expressionism back in university. Internet was shit in my frickin’ rented room, so I bought a lot of canvases, bought a lot of acrylic and oil paint, and I did a lot of painting back then. I would love to go back to that, and hopefully teach my daughter how to do that as well.”

At any mention of his daughter, Vix visibly softens and brightens at the same time. It’s clear that fatherhood has had a profound effect on him, so I have to ask — how does he feel becoming a dad has changed him as a person? “Oh… how,” he says. He pauses, thoughtful, then continues, “I think everything changed. I think… it’s strange, you know — Kanye West had an album called [The Life of] Pablo (2016), and he released that after having his firstborn. Jay-Z dropped an album called 4:44 (2017), which also touched about being a father. I loved both albums even before being a dad, and I sorta get it, like, okay, fatherhood makes you a bit more reflective, a bit more calm. But they did not prepare me for how sensitive you become. Like, I became sensitive to everything — things I was saying, things I hear people saying. I became so sensitive about society, from how little boys are addressing little girls, the things little girls are exposed to at the toy shop, food, everything. Like, everything changes. It’s crazy. You suddenly factor — or you try to factor — everything for the child’s eyes, or for the child’s life. I started reading nutritional labels more. The amount of time I spent on Google just researching stuff, it’s crazy. And you say like, good, bad, good, bad, yes, no, this needs to change, that’s good, that’s bad.” He points animatedly in all directions to illustrate his point. “So suddenly you see the world with a very different perspective. And it’s not even intentional, it just happens automatically. It was crazy — when Kaia was three or four months old, we always made sure the house was quiet,” he says, lowering his voice. “And when I went out to get groceries…” He chuckles at the memory. “When someone were to drop something, I’d be like, ‘SSSHHH!’” He tenses up comically. “You know? You become like, ‘You’re gonna wake Kaia up!’ Although she’s not even there, she’s at home!

“I think it’s changed me in a lot of ways. Perspectives and sentiments have changed, drastically. How I view my family, my wife, myself… also your own family. Like suddenly, seeing your parents, you go like, holy shit, you guys went through this? And then you think about your grandparents, you go like, holy shit, you have eight of this? Like, what?? What were you thinking?! We have one and we’re like, awww, this is crazy!” He laughs. “And then you have an appreciation for everything. It’s positive, really.”

With the birth of his daughter, his priorities shifted, and he found himself looking at himself and his creativity in a whole new light. “I used to wonder — back in the day I looked at musicians and artists and whatnot like, ahh, they drop after they become parents. They’re not creative anymore, and they just got lazy. And then you realise that it’s not that, it’s priorities. Suddenly there’s something bigger than yourself, there’s something bigger than this craft or this legacy of art that you’re trying to leave. And it’s this kid. I think it changed me drastically, for the better, I have to say. You become much more critical about yourself, as well. You start to realise, like, shit, I’ve been a bad person, or I’m an asshole, or I can’t believe I have this out there, and I can’t believe I said this. So you begin to reflect, and from a bigger perspective you start to realise how everything made sense, and how everything had to be for this to be, and you wouldn’t change it for the world. Suddenly you think like, oh, if I were to change this particular thing, or if that particular event did not happen, this kid would not exist. And then you go like, okay, I would change nothing. Like, nothing. If God were to give you a chance, like, hey, if there’s one thing you would change, an event in your life, I would literally change nothing. Because hey, here’s Kaia! You know? So yeah, it’s amazing. It makes you wanna be a better person.”

At the same time, having a child has made him a lot more concerned about the future of the world. “I worry a lot about the future. I think there are a lot of issues in the world that need to be ironed out. Like, not joking — one of the conversations I had with my missus when planning a child was whether we even want to bring a life to this world, because the world is so fucked up right now. But I think what prevailed was hope, and knowing that humanity will eventually sort things out, like we always do. And right now, I’m very hopeful, cause the new generation, they’re being so vocal. We’re having so many difficult conversations right now in the world, even in Malaysia. And they are necessary. Obviously there will always be pushback — change will always have pushback, and that’s fine. But at least the wheels are in motion, conversations are being had. These are things that me and my friends used to speak about in the privacy of our home, because you can’t say these things in a mamak [in case someone hears you]. And now these conversations are in the mainstream, and they’re on Twitter, and people are actually engaging, and if you say something stupid, people will basically say you’re a dumbass. And that’s great. So I think change will happen, I think the world will be better. And consciously I’m trying to see if I can contribute in any way. That doesn’t mean I have to be an activist and go out there and basically be the change — I mean, be a catalyst of the particular force that will change everything — but I think adding momentum to that force, adding voice or adding volume or amplifying it is already a good start. Obviously I hope to do more. The purpose right now is actually, if it doesn’t benefit my daughter, or if it’s something that’s detrimental to her future, it’s something that I’m against. And that is a sentiment that I have never had before this, because it was always myself, myself, myself. It’s funny — back in the day I was like, ‘Ehh! I don’t care about the future, I’ll die one day, I’ll return to the soil, fuck these kids.’ And right now it’s like, ‘Awwhh shittt, the ice caps are melting! No polar bears ever again, nooooo!’” He laughs. “Yeah, so it’s a very different perspective, and a very different motivation right now, on what I wanna do and achieve.”

One of the issues that Vix considers close to home, and has been very vocal about in the past, is racism. It’s a topic he’s drawn attention to through his music (songs like “Keling In ’Em” and “Unwelcomed” are good examples) through social experiments he’s written and designed for advertising campaigns, and through social media. In light of all the events that have transpired recently, and the attention the Black Lives Matter movement has garnered both for its own cause and the causes of other marginalised communities, I’m curious to know how he feels about the current climate. He has a lot to say on the topic. “I think racism has always been there,” he says with a sigh. “It’s not new. I think we’re just seeing it more right now on social media. And I think it often stems from the fact that people live in bubbles, and they just don’t know better. It’s ignorance, really. I think people who have not been exposed to other races, other ethnicities, they live their life pinning a stereotype on that particular person, and it’s often, unfortunately, negative. But it’s ignorance, I think.”

He reflects on his experience in a Chinese vernacular school, where he completed his primary education. Because of his mixed parentage, he — and the one other Indian boy in his year — “stood out like a sore thumb” among his Chinese schoolmates. Though he was teased and jeered at for the colour of his skin back then, he didn’t consider it racism, exactly. “I mean, they were kids. Like, you have to understand that if they were to say anything, it did not necessarily have a bad intent. There’s this whole plethora of stereotypes and fears of like, ‘Oh shit, if I hang out with the Indian kid he’s gonna bash me up,’ or, ‘The Malay kid, he’s gonna say something mean.’ You know, these kinds of things that have been perpetuated by parents in a home environment. It just projects itself and manifests in these kids in school.” However, he did request that he continue his secondary education in a public, mixed race school. Having grown up in government quarters with mostly Malay and Indian neighbours, he wanted to know what it would be like to study in that environment, too. “So in high school I made the switch, and I went to a Sekolah Kebangsaan, and my eyes opened up. I think I realised what I was missing out on. [And] when I made the switch, I wasn’t the only one from my school that made the switch. [And] after a year maximum I think, I saw the other friends that were from the Chinese schools, they assimilated pretty well. They opened up and realised that hey, it’s actually not too bad, and it’s actually pretty nice. Which is why until today I’m a very strong proponent of — I think we should have just one stream of school. For the first time in a school environment I saw Chinese kids were cool with the Indian kids, with the Malay kids. Obviously there [were] the different puak-puaks (cliques, groups) around, and that’s normal, but at least everyone was exposed [to] and comfortable with each other. In Chinese school it was very different. I’m pretty sure it happens if you have a Sekolah Agama (religious school) as well, or a Tamil school — they’re gonna have narratives and conversations and things they say there that [are] not addressed, simply because they don’t know any better or they’re not exposed. It’s crazy.”

“In regards to how the narrative is being steered right now,” he continues, “I don’t fully agree with it. Shouting and screaming at the top of your lungs to someone will never change someone’s opinion. Like, I shout at you, you shout at me — nothing’s gonna happen. If anything, it’s gonna aggravate the situation. I think conversations, calm conversations, need to be had, and I think this needs to be led by community leaders. Unfortunately, I also think racism is highly politicised. I think generally people are good — I like to believe, rather naively, people are generally good people. But there are triggers, and there are narratives, and there is fear mongering that makes you scared, that makes you spiteful. I think conversations need to be had in households, conversations need to be had by community leaders, and because it’s being politicised, those conversations very often don’t take place. There’s always the perception that because you’re standing up for [your] community, you’re gonna step on mine. Which is not the case. Just because I want to empower my people, doesn’t mean I’m gonna shit on yours.

“But that’s what we’ve been fed though, right? It’s like, ‘Awh, those guys want more Chinese and Indians in universities, and in UiTM! Holy shit, they wanna take away your Malay rights!’” he says, referring to the UiTM (Universiti Teknologi Mara) student protest against opening the university up to non-Bumiputera students back in 2018. “It’s ridiculous. I always think the education thing — I’m very passionate about that particular issue. It’s stupid, cause, just build more universities! Just make the university bigger! Instead of spending so much money building another mall, let’s build something that empowers the people, you know?

“But yeah, I think racism is an issue we need to solve. My personal experience with racism — plenty. Again, I think it stems from ignorance. I get stared at — my family, my parents get stared at so much. My parents actually eloped because both sides of the family basically were like, ‘You wanna do what now? With who? Nah, nah, nah.’ So I think they’ve had a much rougher experience than I have, especially in those days. But for me… I had a really close friend that called me pendatang,” he says heavily, referring to the Malay term for “immigrant” which is so often used to describe and patronise Malaysians of non-Bumiputera descent. “But he believed it. Like, for him, again, it’s because of his upbringing and his point of view. And he meant no malice. But he said, like, ‘Ya la, but you’re a pendatang what, like, your great-grandfather came, etc.’ And I get it, but I had to have a conversation with him on how you cannot say that.”

It’s not the loud, in-your-face forms of racism that bother Vix the most — it’s the subtle prejudices and fears people have. “I think the calling out names is problematic, of course, but it’s the one[s] that you do not see or hear — that’s the scary one for me. Like, you apply for a job [and don’t get it because of your race], or the lady stepping two steps behind because you’re in the lift with her, those kinds of things. Those things happen, I’ve experienced it — as stereotypical as they are, those things happen. I have a condo in Mont Kiara — I’m the landlord. I stepped into the lift, and the guard told me to get out and use the service lift. Because I’m dark! Obviously that guy got an earful from me,” he laughs. “But, you know, it’s little things like that that really trigger me, I think. It’s not even the calling out. Like, on Twitter, I understand. People [are] mean, but that’s the nature of it — it’s a frickin’ cesspool there. But it’s the little nuances and the ones where people are unaware they’re even being racist, that’s the scary one, you know? And I think conversations need to take place. And conversations are taking place, and I’m happy that it’s taking place.”

Vix is vocal about racism not just because of his own experiences, but because of what he sees his friends and family going through. “It’s been a topic that I’ve been very passionate about, simply because I see it, and I hear about it too. I know Malays are also victims, I know Chinese people are also victims, and coming from a Chindian family, and having really close Malay friends… like, I see it, and I hear the story about it. So I know it’s not one-sided, I know everyone suffers. I know every race has their pain points. But everyone talks about it so discreetly within their community, and the result that often comes out of it is, ‘It’s that person’s fault, or it’s that person’s fault.’ They blame the whole community when one particular person does something bad, and that’s horrible.” However, he remains hopeful that things will change for the better, because of the conversations that are being led and had by the new generation. “I have faith in the youth. I think the new generation gets it. They’re exposed more, or at least they’re more open to have that conversation in a sense, so that’s great.”

With that in mind, what are some of the changes he’d like to see during his lifetime? “Ah! Well, [a] more united Malaysia would be amazing. We just need to basically be Malaysians. I would like to see that happen in my lifetime. I would like to see the end of bigotry though. More understanding — I think that would be the most ultimate ‘Miss World’ answer I could give. Like, everyone just comes together and stops hating on each other. I think we’re getting there — I’m not sure whether I’ll see it in my lifetime, but things are moving fairly quickly right now. Let’s see. Let’s see.”

Change is indeed happening at a crazy rapid pace. As we speak, our world is changing in ways that we cannot fully comprehend, and which may sometimes feel beyond our control. I ask Vix how he feels about that, and how he deals with it. “I think change is inevitable. I think everyone changes all the time, and I think it’s fine to change. People always say find yourself, find yourself, find yourself. Yes, you find yourself, and that’s great, but know that you will continue to change. It’s normal, it’s part of living. New experiences, having new knowledge of things, you expand your mind, and things change, and that’s fine. Bodies change as well, and your physical attributes change, and that’s fine. I think a lot of people are really fixated on projecting an imagery of themselves which they like, of a certain age, and then that’s it. They lose value or they lose sight of the beauty of change.

“I think it’s important to embrace [it]. Welcome change. I think change is a great thing. But also I think you need to be mentally prepared for change. You need to accept that things are gonna change, and you need to know that it’s inevitable, and you will be affected, and you just need to go with the flow. Cause if you try to stay a particular way all the time, and you can’t adapt, then that’s when stress comes in, and you’re gonna have depression and anxiety and whatnot. So I think change is important, change is inevitable, and I think change is a good thing if you learn how to embrace it.”

BRAZEN QUESTIONS

At the end of each interview, we ask our guests a series of BRAZEN questions about what inspires them, in the hope that you will be inspired, too.

What makes you want to get out of bed in the morning?

“Oooh! A sunny day and Kaia, my baby. Yeah, if the day's sunny, that’s it, I’m very happy.”

Who inspires you?

“Who inspires me? Wow... I think poets, artists, painters, writers inspire me. I often read something and get really inspired, be it inspired to do better or inspired to do something, or to craft something, or inspired to change something. Yeah, I’m inspired by the power of words, and art, and craft, very strongly. Also paintings — I love going to the museums and looking and staring at paintings. It always conjures up a sense of inspiration in me.”

Who inspires you to be better?

“Oh, my daughter, for sure. My daughter and my wife. And also my parents, and especially my parents nowadays. Cause I see — now that I understand what they went through, with so little that they had, it makes me appreciate what I have, and it basically heightens the bar of what I want to achieve. Because if they could do this with this little, and I have this much more, I can do so much more. So yeah. Mostly family, really.”

If you could tell Kaia one thing, and have her really take it to heart, what would it be?

“Be true to yourself. I would say that. Yeah. You can never go wrong. You can never go wrong.”

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

“Really boring one, really. My dad told me to work hard, no matter what. Just... he said to succeed, just work hard. And that's it. He told me, because of the scenario in Malaysia, like, being coloured, you just have to work twice as hard to get where they are. And if you want to exceed that, you have to work twice of that. And I've used that for most of my career, really, in advertising. I worked very very very hard. And true enough, it sprouted some really nice things.

“Um... yeah. It's not profound, though — [have I got] anything profound...? I mean, when my grandma told my wife — my grandma had a stroke at that point. She was in bed, she couldn't move, she was very sad. But she told my wife to take care of me, and she also said, ‘Vix has a good heart. He has a good heart inside.’ Now, when she said that, I felt guilty. Because I know myself, that I've done bad things, I've said bad things. And I'm not this saint that she thinks I am. And that has stuck with me. It's not advice, but that phrase has stuck with me because it has made me want to be better. Every day. Like, I hear her saying that all the time in my quiet time. And it makes me want to be better, cause my late grandma has this expectation of her grandson, and I wanna be that person, I would hate to disappoint her. And that's been motivating me. So that's not a piece of advice though, but that's a phrase that has kept me going for the last few years. I'd hate her to be in heaven and someone goes like, ‘Hey, hey, look at that kid!’ Like, ‘Awww fuckkk.’ [laughs] You know? Then when I go up there I get like an earful. [laughs]”

What’s your idea of the fullest version of yourself?

“Oh... fullest version of myself. I am the fullest version of myself right now, as much as I can be. So... yeah. I am the fullest version of myself — I think just being myself is the fullest version of myself. Will I be more than this? Will I be less than this? Maybe, in the future. But then that will be the fullest version of myself then. But this particular moment though? In time? This is the fullest version of myself. I am the best version of me I possibly can based on my circumstances right now, based on my life right now and based on my health right now. And that is what it is, and that will continue to change, too — like, the fullest version of myself in the next two years, five years, ten years will change. But as long as I try to live and try to be the best version of myself, then it is what it is. Yeah.”

What is your proudest achievement so far?

“My proudest achievement in life is to basically be true to myself, and being able to face myself, and keep that childlike wonder, you know? Like, I'm very proud that I have not allowed the world to dictate too much on how I perceive myself or how I judge myself. Which leads to that question of my proudest piece of work. I don't think it's... hmm. I would say my proudest piece of work probably is my first ever painting that I did, in university. It was my first attempt. It marked my first ever piece of work that was truly free from inhibitions. I did not know what abstract art was, I didn't know what expressionism was at that point, and I was just doing it. It took me a few years later to realise, like, wait a minute, what I did was actually this. That is my proudest work, I think. And my proudest achievement is basically, yeah, like what I answered before, you know. Being able to free myself from the shackles of society and perception and social media and whatnot. Like, I've done so many embarrassing things — publicly. [laughs] I've been judged on so many things. But I did not let it faze me, and I think that is great. I think for a lot of people, that might just sink your boat and that's it, you know — you become a hermit for the rest of your life. And I'm really proud that for me I'm able to — well, not rise from the ashes, but evolve. And learn from it, and take something good out of it. Yeah. That's my achievement, I think.”

Was it a conscious decision, to go back to that childlike wonder?

“No. No, no, I think that was not a conscious decision. I think that was just me being brave, I think. Cause I think a lot of these pursuits, I had nothing to lose. I mean, if I didn't like the outcome then I don't have to show it to anyone, so there was literally nothing to lose. And I was just having fun, really. And that goes for all of my work — be it writing, be it painting, be it music. I just dive in and just wonder, what would it be and just go for it. I've always had this fear of being 70 or 80 years old and regretting not doing a lot of things. I think that's a horrible feeling. Rather do it and regret, than not do it at all, I think. I think that would be my best approach when it comes to creative things. Just try. And at least you can — and even if it fails, you have a story and you have an experience that you can share, or you can cherish or you can learn from. So it's never really a lose-lose situation, if you put yourself out there.

“It's scary! It's scary when you had the opportunities to do so many things... I think a lot of people do not realise, or do not value the opportunities they have, until it's taken away. Like, I know I'm blessed to be able to have the mind, the voice, the means to make music, or to paint or to write or whatever, you know? It is a privilege, cause not everyone has that. So when you have the means, say yes and just do it, you know? If it works out, that's great, if it doesn't work out, that's fine, too. But at least you've done it, you know? But also don't be FOMO though. Like, growing up I [was] always like, ah, I want to have the experience of jumping off, free falling from a plane, simply because, you know, that's living life. But I'm fucking afraid of heights. So now that I'm older I'm like, 'Ehhh, I probably can afford it, and can do it, but I wouldn't wanna because nah, it doesn't... I don't wanna.' I don't think it's something I'll regret when I'm 80. [laughs]

“I have a line in one of the songs [on the new album] called... I think ‘Motivation.’ It says, 'Everybody can dream a little dream / But how many chase them with their eyes peeled / I chase bigger dreams / But chase only dreams you feel.' So obviously there's a lot of things you can have in your to-do list, but a lot of things are nice to have or for brag rights, and you should only pursue dreams and ambitions that you're really passionate [about] and really mean something to you. I can't remember, what song was that? I think that's ‘Motivation’... I'm not sure. I have all my lyrics jumbled up, so I'm not sure. [laughs]”

If the Vix you were ten years ago could see you now, what would he say?

“‘What the fuck happened to you? [laughs] What's with the dad bod, bro??’ Ten years ago... he would say well done. I would like to think he would say well done. I mean, I achieved most of everything I wanted to achieve ten years ago. So creatively, career-wise, in terms of my personal life, exorcising all my demons, being able to look myself in the mirror and not look away every two seconds and go like, ‘I couldn't face you.’ Yeah, I think he would say, ‘That's great, I wish I could fast forward time.’ And I would tell him back, ‘I wish I could reverse time and go back to your age.’ And probably drink more. I am horrible at drinking right now, like, I cannot drink. Two glasses of wine and I get a hangover. So he would probably be unappreciative of that. [laughs]”

What would you say to him?

“Nah, I think... I think I would just say just do you. I would say that to anyone, really. Just be true to yourself. Speak your truth, act your truth — you can go no wrong that way, I think. I think in the process of finding yourself when you're younger, obviously you try a lot of different pants, try to wear very different hats, and that's fine. But the purpose and the intent should be to find one that you're comfortable in, and that makes you happy rather than something that, I don't know, makes you project something that's cool to your friends, or that helps you elevate to a certain social status or whatever not. I think those are wrong motivations. I think it's just be really true to who you are, have that self conversation with yourself, and face up. And that's a hard thing to do, from personal experience. I think having to actually look yourself in the mirror and say, ‘You're this, you're that, you're this, you're that,’ or ‘This is what you need to work on,’ and whatnot, and ‘I shouldn't have done that,’ whatever not. It’s easier to find excuses or blame it on external reasons and factors. And sure, they have their influence on you, but at the end, it's important to face yourself, and find your truth and act your truth. And when you do, then everything makes sense and you're generally just happy, cause you're unshakeable.”

Who is someone inspiring change in the world right now that you’d like to give a shout out to?

“The youth, really. It's not even a big figure. Like, I have no big figure in my head that's doing big changes. I think change comes with little changes, and I think the youth are doing an amazing job at that. There's no reservations on voicing things out, or trying to make things happen. Also I think they have all the tools in the world right now, because of the internet. And they're doing it without thinking twice. I think they're the strongest catalysts of change, and I think for Kaia's generation, that's gonna be even stronger. And I have complete trust that they will do the right thing. Old people... I mean, I dunno. I have doubts on figures who do good and then publicise about it. I mean... they might have external motivations, but plus I also do not look at anyone in particular that's super iconic and go like, ‘Man, you're the guy.’ I think it's the ordinary people doing the ordinary things, and trying to do extraordinary feats. Those are the ones that will really make a difference. So shout out to the youth!”

What is something you hope never changes?

“Ah, innocence. I think children need to have childhood. I think let children be children, let them play. I think we shouldn't... it's already happening in Asia, tiger moms and whatnot, but I think we shouldn't chart how kids should turn out too much. I think children should have their freedom and innocence to continue to play, to discover, to learn and to experience. I hope that never changes.”